How to navigate Zygmunt Bauman’s liquid world

“If we wish them to become truly familiar, apparently familiar things need first to be made strange.” – Zygmunt Bauman

Your newsfeed has more stuff than you want or can read, daily. Your Whatsapp receive a lot of messages while you use Tinder to find a new date. We can travel anywhere and you just have to download something like Uber to have a driver waiting at your front door to take you to the airport while you do the check-in from your smartphone. All of this is reality to some people, but it’s a recent truth and it may not last. It’s this fluidity of the modern life and the meltdown of relations that Zygmunt Bauman study to give us some understanding of it.

Bauman is a polish sociologist who studies modern society, ranging from politics, through consumism and art. In his book “44 Letters from the Liquid Modern World” he compiles texts written from 2008 to 2009 for the magazine La Repubblica delle Donne. In these letters he introduces themes of this liquid world that seem familiar to us and try to help us understand them beyond our daily lives. His transition to the study of post-modernity is marked by the appearance of the term modern liquid world:

“From the ‘liquid modern’ world: that means from the world you and I, the writer of forthcoming letters and their possible/ probable/hoped for readers, share. The world I call ‘liquid’ because, like all liquids, it cannot stand still and keep its shape for long. Everything or almost everything in this world of ours keeps changing: fashions we follow and the objects of our attention (constantly shifting attention, today drawn away from things and events that attracted it yesterday, and to be drawn away tomorrow from things and events that excite us today), things we dream of and things we fear, things we desire and things we loathe, reasons to be hopeful and reasons to be apprehensive.”

The example I gave in the beginning is only the surface of the world as seen by Bauman, the changes occur in all areas and our anxieties tend to come even from the mere possibility of change:

“To cut a long story short: this world, our liquid modern world, keeps surprising us: what seems certain and proper today may well appear futile, fanciful or a regrettable mistake tomorrow. We suspect that this may happen, so we feel that – like the world that is our home – we, its residents, and intermittently its designers, actors, users and casualties, need to be constantly ready to change: we all need to be, as the currently fashionable word suggests, ‘flexible’. So we crave more information about what is going on and what is likely to happen. Fortunately, we now have what our parents could not even imagine: we have the internet and the world-wide web, we have ‘information highways’ connecting us promptly, ‘in real time’, to every nook and cranny of the planet, and all that inside these handy pocket-size mobile phones or iPods, within our reach day and night and moving wherever we do. Fortunately? Alas, perhaps not that fortunately after all, since the bane of insufficient information that made our parents suffer has been replaced by the yet more awesome bane of a flood of information which threatens to drown us and makes swimming or diving (as distinct from drifting or surfing) all but impossible. How to sift the news that counts and matters from the heaps of useless and irrelevant rubbish? How to derive meaningful messages from senseless noise? In the hubbub of contradictory opinions and suggestions we seem to lack a threshing machine that might help us separate the grains of truth and of the worthwhile from the chaff of lies, illusion, rubbish and waste . . .”

To understand or at least to have better tools to navigate this liquid world, Bauman seeks help from Walter Benjamin to propose two narrative forms. One of them is the narrative about bizarre actions and heroic deeds, those that are fabulous and have little to do with their listeners, the other one is the narrative of closer events, stories of the daily life that seem common, familiar. To Bauman even the more common and simpler stories can only be apparently familiar:

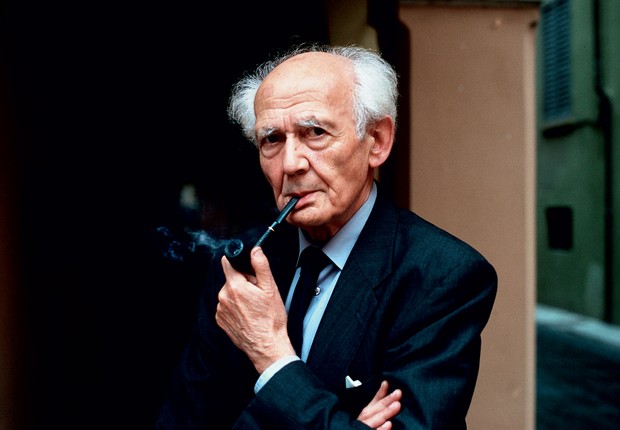

Zygmunt Bauman

“I said apparently familiar, since the impression of knowing such things thoroughly, inside out, and therefore expecting there to be nothing new to be learned from and about them, is also an illusion – in this case coming precisely from their being too close to the eye to see them clearly for what they are. Nothing escapes scrutiny so nimbly, resolutely and stubbornly as ‘things at hand’, things ‘always there’, ‘never changing’. They are, so to speak, ‘hiding in the light’ – the light of deceptive and misleading familiarity! Their ordinariness is a blind, discouraging all scrutiny. To make them into objects of interest and close examination they must first be cut off and torn away from that sense-blunting, cosy yet vicious cycle of routine quotidianity. They must first be set aside and kept at a distance before scanning them properly can become conceivable: the bluff of their alleged ‘ordinariness’ must be called at the start. And then the mysteries they hide, profuse and profound mysteries – those turning strange and puzzling once you start thinking about them – can be laid bare and explored.”

Bauman’s letters are a way to see while being inside the liquidity:

“Tales drawn from the most ordinary lives, but as a way to reveal and expose the extraordinariness we would otherwise overlook. If we wish them to become truly familiar, apparently familiar things need first to be made strange.”

When he defines the objective of his letters he also tell us what’s a possible objective to any intellectual endeavor, even if it demands a great effort to distinguish the signal from the noise. “44 Letters from the Liquid Modern World” is one of those rare books where the clarity don’t compromise the depth of the text.

Other recommended Reading that was already presented here is about how the world we create acts back on us and recreates us, the original article is written by Anne-Marie Willis.