Voyeurism and the blurred reality in the paintings of Edward Hopper

"but in boredom is exactly when we feel time and being the most acutely. It can inspire a profound mood, maybe that’s what these people are feeling."

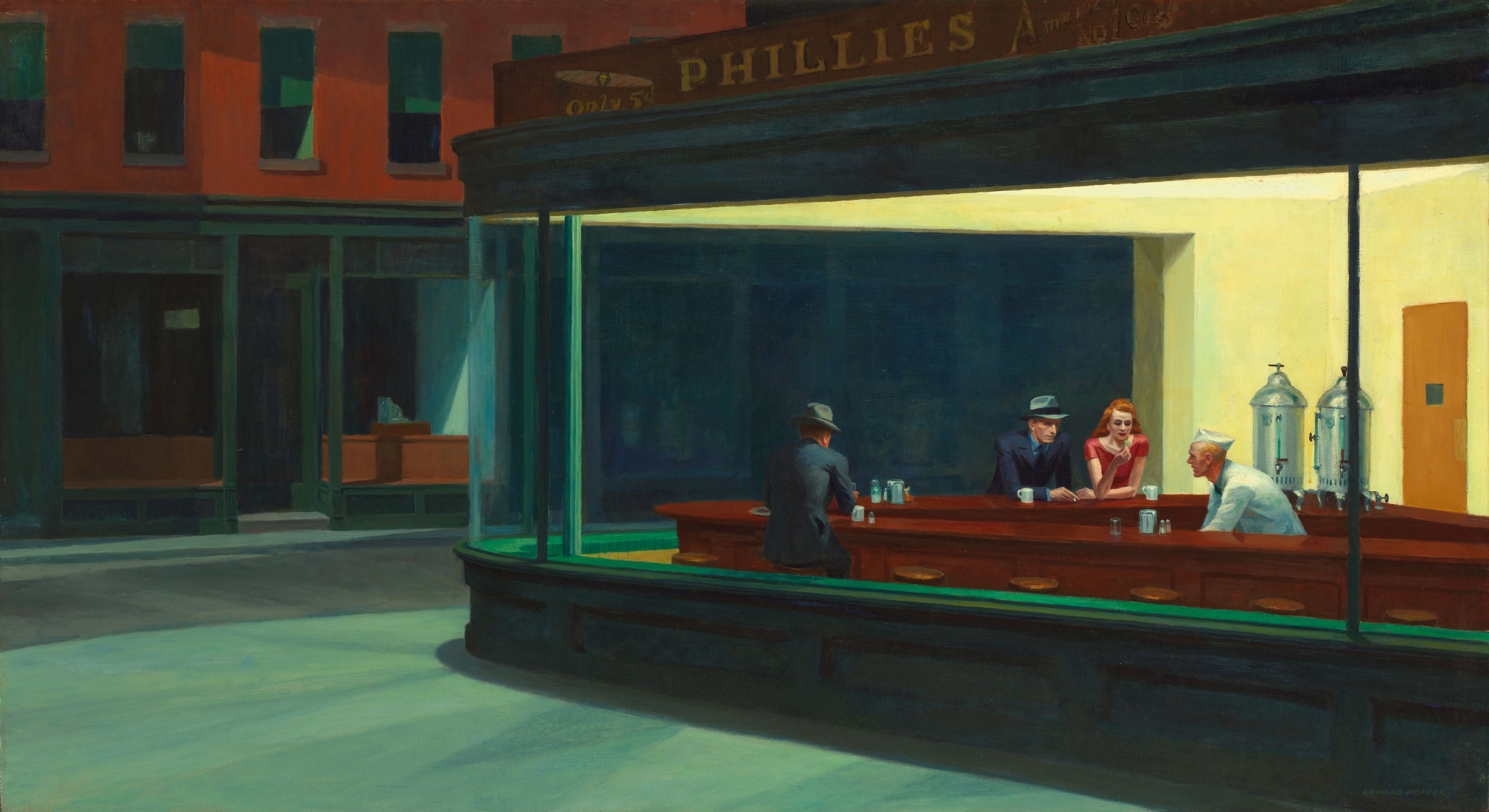

The darkness of the night, a bar still open, lonely meeting place in a desert street. You already saw a painting like this. It has a way of seeing the world that unwittingly penetrates our lives. As in other paintings made by Edward Hopper, in Nighthawks we face a bar highlighted by it’s own lights with distracted and absorbed people in the interior.

"Nighthawks". Edward Hopper, 1942. Oil on canvas.

Evan Puschak from the Nerdwriter channel posted an analysis of this most famous painting from Hopper. He begins by remarking the sense of realism in the paintings, however without being enforced by the technique since there isn’t an interesting in photorealistic representation. The sense of truth comes exactly from the blurred details that allows everything to become more universal:

“But pulled back by one degree to depictions slightly more generalized, slightly more detached from place, history and person. In this way there’s just enough room to put your own life into Hopper’s work, but once inside it’s impossible not to be closed in and see that life along his themes.”

Selfportrait. Edward Hopper, 1930. Oil on canvas.

With Hopper these people become possible representations of ourselves, a space of our lives unfolding in the canvas as we observe from outside. Nevertheless, it is not only about observing, there is a certain interaction connected with the voyeur, of seeing something very personal without the permission from the other person. An invasion that is possible only because it is anonymous, but also because it grants a way of seeing someone acting freely exactly due to the unconsciousness of being watched.

“His subjects were both behind and in front of windows. Of course windows are the place where the separation between outside and inside becomes complicated and not because we can physically move through them but because our sight does, because our gaze invades these private worlds. Indeed, in Hopper’s works the windows appears as if they’re not even there.”

Evan Pushak reminds us of the long effort that Hopper used to dedicate to each one of his paintings. From the studies and sketches to the final version of work he could takes months and this must be remembered to evaluate his paintings:

“Hopper wanted his devotion to each work to be mirrored by our appreciation. As slowly and deliberately as he painted he wanted us to look, really look, to be made vulnerable as a viewer always is whether he or she is crouching in the dark in the building opposite or simply crossing the street.”

At the time when the Nighthawks was painted there was in the USA the routine of turning off the lights during the nights. The reason was the recent attack to Pearl Harbor and the fear of new attacks got people trying to “hide” the city lights at night to make the possible targets harder to notice. However, Hopper never turned off nor concealed the lights of his studio where he spent the nights painting. Nights that allowed the creation of the Nighthawks, the image of the last light of the street, seen by someone crossing it.

“The light in the Nighthawks dinner seems to be the last light still shining in the city. And for this reason I think you can find a slightly more optimistic reading about this painting. What else is there to do in the face of great disquiet and doubt but work and live on? All of Hopper’s people seem to be huddled up against the present moment. Lonely? Yes. Waiting? Maybe a little bored? People of the Nighthawks are no different, but in boredom is exactly when we feel time and being the most acutely. It can inspire a profound mood, maybe that’s what these people are feeling. Alone together in their lighted ship sailing against the darkness of all the darkness that was yet to come. The yellowish, greenish, fluorescent light in this scene like the light in the Hopper’s studio is a meager substitute for the brilliance of the sun, but it can though giant windows still illuminate the world.”

In a profound evaluation of the image, Susan Sontag shows us the relation between the real and the images we create, relations that are as powerful as they are subtle. An extension between the painter’s life and the art implies that even due to an unconscious impulse there is a lot of its historical time in each work. Nevertheless, maybe the reason why they last so much time and are important to so many different people is what they have of less obvious and more universal, the suggestion that Edgar Allan Poe used to talk about.

This video is part of the series “Understanding art” from the Nerdwriter channel. Watch the full video below: